http://invisible-island.net/

Copyright © 2005-2013,2014 by Thomas E. Dickey

The book Solaris Systems Programming by Rich Teer borrows ideas, organization and content from Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment by W. Richard Stevens. However that fact is not reflected in its bibliography. This summarizes my own observations as well as comments by others on the topic.

The works discussed here are:

Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment. W. Richard Stevens. 1992. ISBN: 0-201-56317-7

and

Solaris Systems Programming. Rich Teer. 2005. ISBN: 0-201-75039-2

To explain why/how I noticed this issue: there was a long newsgroup argument which I had been following for the past month (December 2004). There was a comment by one of the posters which said in rather strong terms that the latter book was required reading. While I may not agree with that, I thought it best to study the book to defend my opinion. I had noticed it in a nearby bookstore, but (on first glance) it was not something I needed (Stevens book is very good).

Going back to the book, I went to the section that I had looked at before; which discusses a section where I'm an expert (see my webpage). Two things were odd about the section: the phrasing of the final paragraph did not mesh well with the rest of the section. But more obvious was citing Goodheart, who's been out of print several years. Using an old reference like that for a new book – and then commenting that the whole topic is becoming obsolete seemed inconsistent.

I went to the bibliography to check Goodheart – 1991 (page 1154 of Teer). Reading down the bibliography, I noticed on page 1156 that Stevens was cited. But there is something odd about that citation. It mentions the three editions of Stevens UNIX Network Programming. I do not have that book; I am familiar with the material covered, and it was odd that Teer would cite three editions of that when it is not a focus of Teer's book. But Stevens Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment is (except for the focus on Solaris) much the same type of book. Teer does not mention this book in his bibliography.

Next I looked at the preface and introduction. Teer mentions Stevens in one line (bottom of page xxxv), for inspiration. The introduction does not give any credits; those are all in the preface.

However, I was in the bookstore. Teer's book was on the top shelf; there was a copy of Stevens on the preceding bottom shelf. I picked that up, and opened it to the table of contents. To a first glance, it was the same table of contents as Teer's: there are differences, but more similarities than difference – most of the section titles in Teer are the same, or a word different from Stevens. The chapter ordering is mostly the same, making the similarity more striking.

I went to the section in Stevens which I had looked at in Teer. Starting at the bottom of page 504 (Teer), and comparing with section 11.13 in Stevens (top of page 360), I found the same ideas, much of the same wording transferred from Stevens to Teer.

Seeing the two sections, and the table of contents, I selected another section (don't recall which), and noticing that they also were similar, decided to buy Teer's book so that I could discuss it further.

On the newsgroup, I asked:

Speaking of which - since you're determined to force it upon everyone's

attention:

Since that borrows (more than a small amount) upon

"Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment",

W. Richard Stevens, 1993

why does its bibliography only mention Steven's 3 editions

of "Unix Network Programming"?

His response (in part – both quotes via google, though I have copies saved via my newsreader):

My book doesn't "borrow" from APUE, certainly not to the extent that you seem to be implying. Both my book and APUE cover a similar subject (one might argue that SSP is in fact a superset of APUE), and I admire Rich Stevens' writing style--a style that in the sincerest form of flattery, I've attempted to immitate (I'll take your words as a sign that I was somewhat successful in that attempt). It shouldn't be too surprising, then, that the two books appear to be at least superficially similar. > why does its bibliography only mention Steven's 3 editions of > "Unix Network Programming"? Because my book doesn't make reference to Rich Stevens' other books. If it did, a suitable reference would be in the bibliography.

That was clear enough. But my dictionary says

plagiarism act of stealing and using as one's own the ideas or the expression of the ideas of another.

I started comparing the two books side-by-side, and in a half hour found that most of the sections I compared had borrowed (rewording, but retaining most of the original). Not all sections in Teer's book borrow from Stevens, but my initial impression (having spent a few hours on this) was that if Stevens had something to say that was relevant to Teer's book, it can be found paraphrased there. There are also a number of instances where it is not paraphrased, but used without change.

Here is the example I noticed first. It is from Teer (bottom of page 504 to middle of 505). Close study indicates several problems with grammar and word choice. I have emphasized a few of the ones that I see. Compare to Stevens (second paragraph of page 360, to the end of section 11.13):

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One might argue that was coincidence, an isolated example. To deal with that, it is necessary to review the whole book. Here are (briefly) the findings from that review. But it is a long list, thus relegated to an appendix.

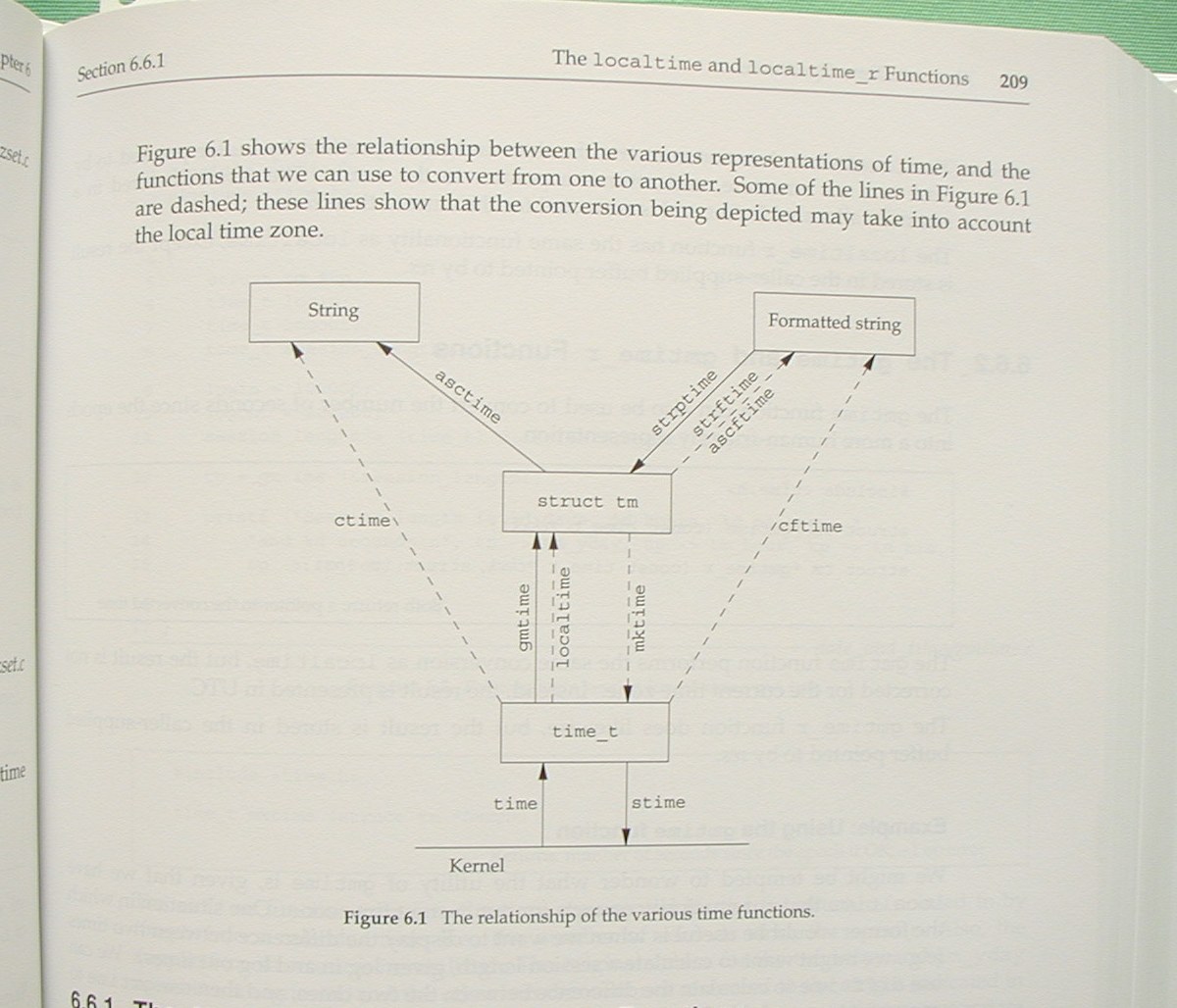

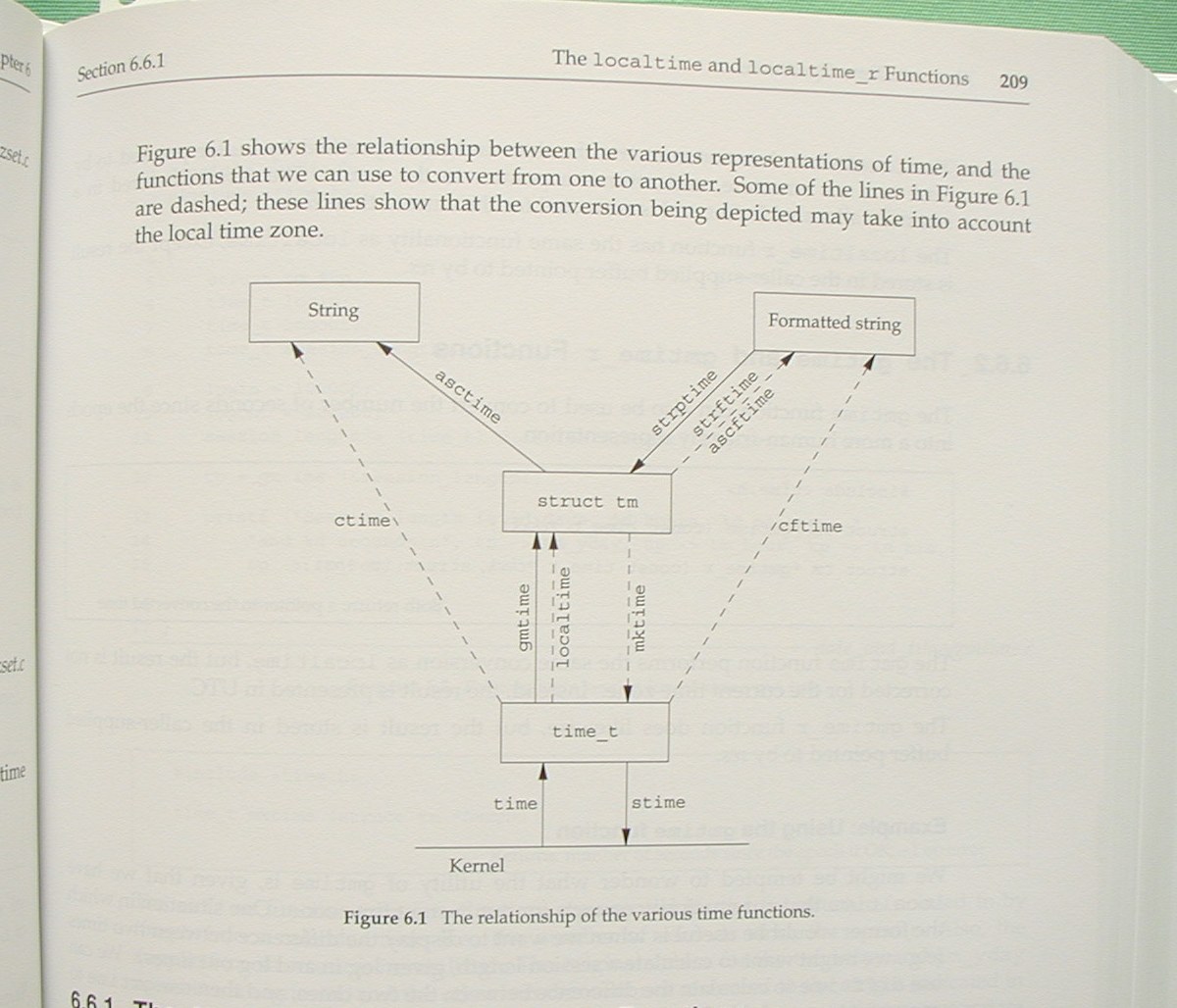

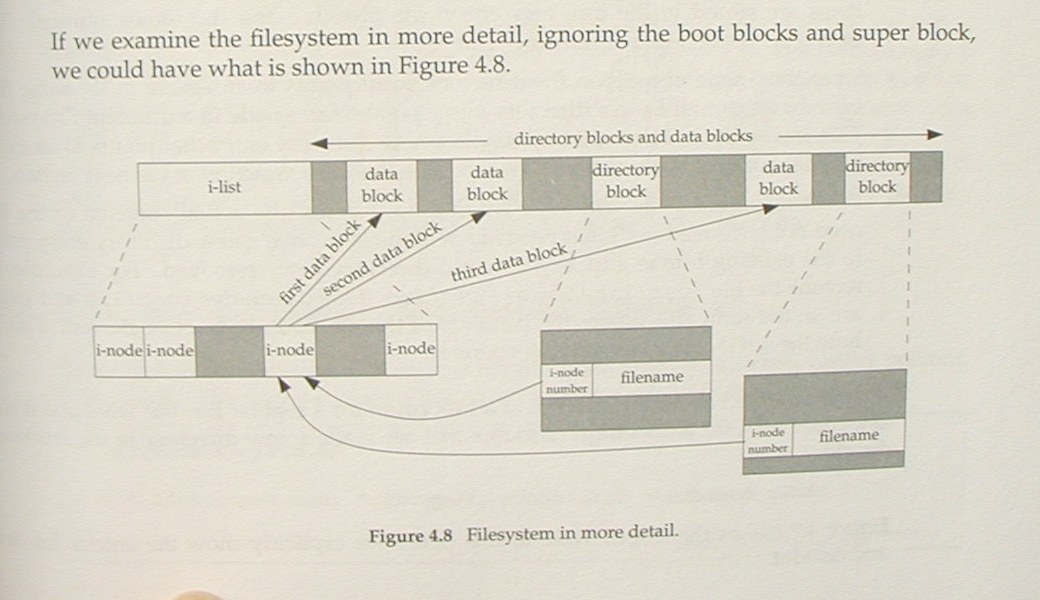

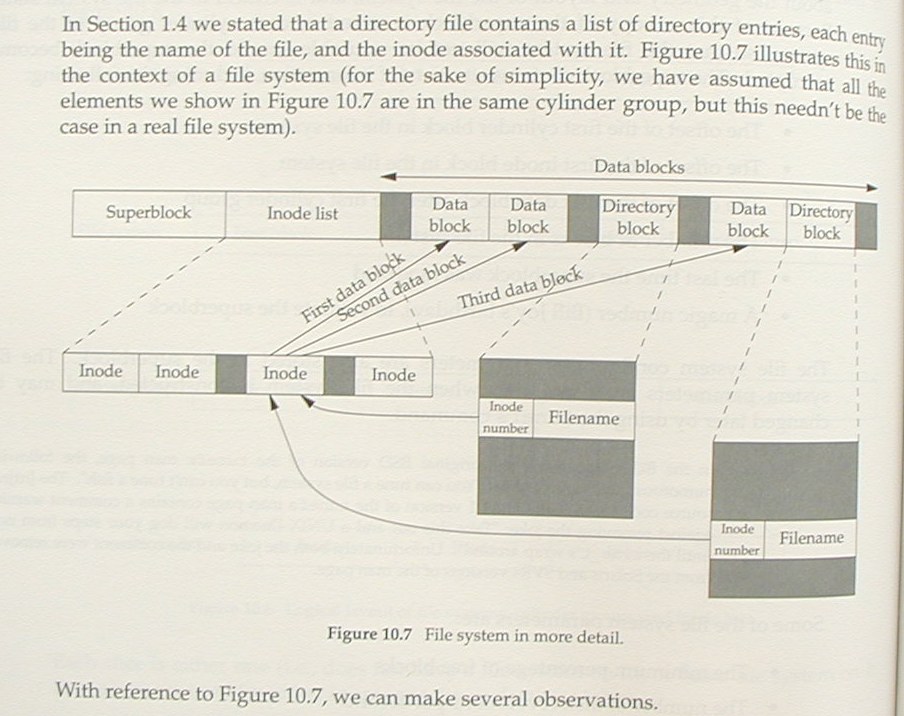

At first glance, perhaps different. But look again. The layout of Teer's figure is the same as Stevens'. Some information (Solaris-specific) is added, but most of the difference lies in the fact that Teer's copy is larger.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

To avoid breaking up the flow of discussion, other figures can be found here.

Searching for "Solaris Systems Programming" with google, the first hit (other than Rich Teer's webpage) is the advertisement on amazon.com. The page lists five (5) reviews. Four (4) are favourable. But reconsider them:

This search yields some interesting insight here, here, and here. To read Rockwood's review in the context of its intended audience, read slashdot.

The remaining review is unfavorable. In short, it notes that the book is of mediocre quality. Talking to Gunnar Ritter about this, I find that he has much more to say about that aspect than I am likely to. Rather than dissect Rich Teer's mistakes in rewording Richard Stevens' text, I have included Gunnar Ritter's comments as an appendix.

Several technical reviewers are cited in the acknowledgements. One may ask why none of them brought up this problem. Some of my associates have offered these possible explanations:

The preface notes that one person actually read the whole manuscript.

See this newsgroup thread for a discussion of the borrowing from Steven's book. Some of the newsgroup readers have both books, and their remarks are insightful:

Do you mean what I think you do? Looking at the two books I now start to see what I think you mean. I looked at Teer chapter 16 (Process Relationships) and chapter 9 of Stevens Advanced Programming in The Unix Environment: * several paragraphs seem eerily similar in Teer and Stevens (paragraph sequences that match, same order of ideas in paragraphs, even quite similar wording in sentences) * the majority of the diagrams in these chapters are nearly or exactly the same * the section titles are mostly the same, and in the same order * even the titles of the chapters are the same It seems unlikely that could have happened by chance. Comparing chapter 15 of Teer with chapter 8 of Stevens (both called Process Control), in most cases eaqch program in Teer matches one in Stevens, excepting changes in variables names, etc. A rough scan shows other chapters which seem to have remarkable degrees of similarity.

I own them both and have looked at some of the sections you cite. The resemblances are striking; there can be no debate that SSP was written with APUE lying open to the left of the keyboard. The question is how to judge that. Consider that if you look at the source code for Solaris itself you'd find sections which bear a similarly striking resemblance to *BSD. That's not considered plagiarism, it's considered reuse, as long as no licenses are violated. The alternative would be NIH syndrome, also known as Windows.

Though of course that argument fails to persuade Ian Clarke. Henry Townsend also argues that

In Rich's defense, his original mentions of the book (here, a few years ago) referred to the project as an updated edition of APUE. The implication was that he planned to publish it as the second edition WRS would certainly have written had he lived. It was eventually published not by Addison-Wesley, the publisher of APUE, but by Prentice Hall and not by the name APUE Second Edition but Solaris Systems Programming. Presumably he was unable to get AW, or the estate of WRS, or whoever was the "process group leader", to sign off on the project and had to shop it elsewhere. So I suspect—and note that I have no personal knowledge of any people or organizations involved—that when much of the work on this book was done it was intended to be APUE II.

Though of course the lack of attribution makes that argument awkward.

That some programs become so common and are a part of "UNIX folklore" so that nobody attributes them any more and doesn't say e.g. "Hello world" program was originally written by (say) K&R (I don't really know who wrote that one), reference [1].

Dragan Cvetkovic has more to say in the same vein, for instance this:

Ah, terminfo vs termcaps. Is there a different way to describe that?

As noted by Henry Townsend, Rich Teer more than once referred to the book that he was working on as an updated version of Stevens' book. Google finds 20 references; a few are quoted here to show that they are consistent:

Forgive my indulgence, but I am pleased to announce the publication of my book, Solaris Systems Programming. Despite the word "Solaris" in its title, my book is suitable for programmers of any UNIX or UNIX-like operating system. My vision of this book was one that could be regarded as an updated and expanded version of Rich Stevens' excellent Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment, with a Solaris bias. With all humility, I think I've largely achieved this lofty goal, although time will tell...

On Wed, 9 May 2001, Richard wrote: > A new Solaris programming book, eh? > It's times like this that I really miss Richard Stevens. I miss him too (I was one of the reviewers of UNP 2e, V2). My book will hopefully be as good as Rich's. I use the same tools (vi, groff, tbl, gpic), and my book has the same look and style as Rich's. Imagine a new edition of APUE, which is up to date, and has a (fairly significant) Solaris bias: that's how I envision my book.

On 24 Nov 2000, Andrew Gabriel wrote: > I guess you will be competing with Stevens' Advanced Programming in the > Unix Environment, so you need to think how you can improve on that. Yes, that excellent book will be my main competition. Good as it is, some of the material is a bit dated now. > If you are looking for a Solaris bias, you could think about issues > which are more Solaris-specific and not covered by Stevens' book (i.e. > complimentary rather than competing). The book I'm planning will almost fit both categories. Hopefully, being more up to date, and a Solaris bias will be two good selling points from both points of view. If you already have APUE, a lot of my material will be less important (to be the reference I envisage, some overlap is inevitable), but it will make an ideal complement to APUE. And if you don't already have Rich's book, then maybe my book would be a better choice. > An area which isn't so well covered in books I've scanned through is how > to design software which scales well on Solaris multi-processor systems. > I've seen some projects which made pretty fatal mistakes at the beginning > such that later redesign was necessary. With appropriate initial guidance, > that could easily have been avoided. I will be covering multi-threaded programming. I don't intend my book to be a "how to program" type book, but I think that a section or two about scalable design would be a good thing to include.

Though as two of the reviewers on amazon.com note, threading is not covered.

Teer states repeatedly that he is an admirer of Richard Stevens. Oddly enough, google finds little newsgroup discussion where both Stevens and Teer participated, so that one may gauge their interaction. (A reader of this page found one instance, where Teer does comment about his plans, but it is only Teer adding to one of Stevens's remarks). Since Teer is said to have been a technical reviewer for Stevens' network programming book, presumably there was private correspondence. But that would be irrelevant to this analysis.

The comments which google finds suggest that Rich Teer started his book in late 2000, more than a year after Stevens died. According to Teer's resume, he was working on the book from early 2001 to the end of summer 2004 (he says three and a half years).

The one line in the acknowledgements crediting Stevens reads

Special thanks to W. Richard Stevens for his inspiration and encouragement when this book was just a twinkle in the author's eyes.

At first glance, that might be taken to imply that Teer had discussed his plans for a book with Stevens. However the available evidence suggests that (aside from intentions) the real planning of the book came later.

The book is laid out as if Teer used Stevens' book as an outline. Consistent with that, Teer paraphrased Stevens introductory discussion on several topics. That much warrants an entry in the bibliography.

But Teer also imitates/copies figures from Stevens' book, imitates/adapts/copies programs from Stevens book. Townsend tries to argue that copying the programs is fair use, but see this newsgroup thread, in particular:

I was thinking about the same thing in May 1998 so I asked Mr. Stevens about the copying policy. The question was about sources in UNIX network programming -- 2nd edition and especially about the writen function in Figure 3.15, page 78

and

The reply from the editor was: You have Prentice Hall's permission to use this code snippet as long as you cite your source, do not use this for commercial purposes, and have read and understand the disclaimer in the book. The software is provided on as "as is" basis and without warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, including without limitation any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. In no event shall the author or Prentice Hall be liable for any damanges of any kind as is stated in the disclaimer.

Adapting the programs for use in another book is commercial

use, of course.

Adapting them without credit is plagiarism.

Teer states more than once that he is imitating Stevens style. That is nonsense. Teer is imitating the organization and content of Stevens book.

What should be done?

That depends on the context, of course. Beyond the dictionary definition, plagiarism is a topic that is interesting to many people.

For an academic environment, here is a good overview of the topic. Other online references such as this and this are simpler, aimed at persuading students to not infringe. Much attention is given to copying of content from online sources. But:

For a professional, similar constraints apply. However see this, for the applicable text:

4. Uncredited improper paraphrasing of pages or paragraphs (by changing a few words or phrases or rearranging the original sentence order). Calls for a written apology to avoid suspension of publication privileges and a possible violation notice in the later articles bibliographic record.

It is not clear if that applies to Teer either, though several of his newsgroup postings use the term "professional". But this page for the publisher certainly does.

To whom should Teer apologize? Apparently the publisher (who acts in two roles), and Stevens' family (who would be getting royalties from Stevens books) are the injured parties. People who buy the books also have been defrauded.

Specifically:

Gunnar Ritter provided much detail to substantiate my impression that the book is not well researched. He has also provided useful feedback on this webpage.

Ian Clarke served as a second opinion, making the same arguments and observations that I would.

Several of my associates have offered opinions on this topic (which generally conform to mine). I have noted those as supporting discussion. Since their comments were made via private email and because the comments are short, I have not listed their names.

As indicated in Appendix C, there are many examples from which to choose. Showing all of them would be excessive (for several reasons: time, space, etc.). This is a review, so the selection is small.

Not coincidentally, this is the same section number in both books. Later sections differ by chapter number; borrowed portions still tend to have the same section number within chapters.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

Same concepts, same order of presentation. Teer does move one sentence to a different paragraph.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At first, I did not pay much attention to the exercises. But Teer uses Stevens' material in that area as well.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As indicated in Appendix C, there are many examples from which to choose. Here are a few which are representative of the whole.

The main difference between these two is that Teer added the superblock which Stevens mentions in the paragraph preceding figure 4.8. Labeling, layout (including the choice of crossing arrows) are copied.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

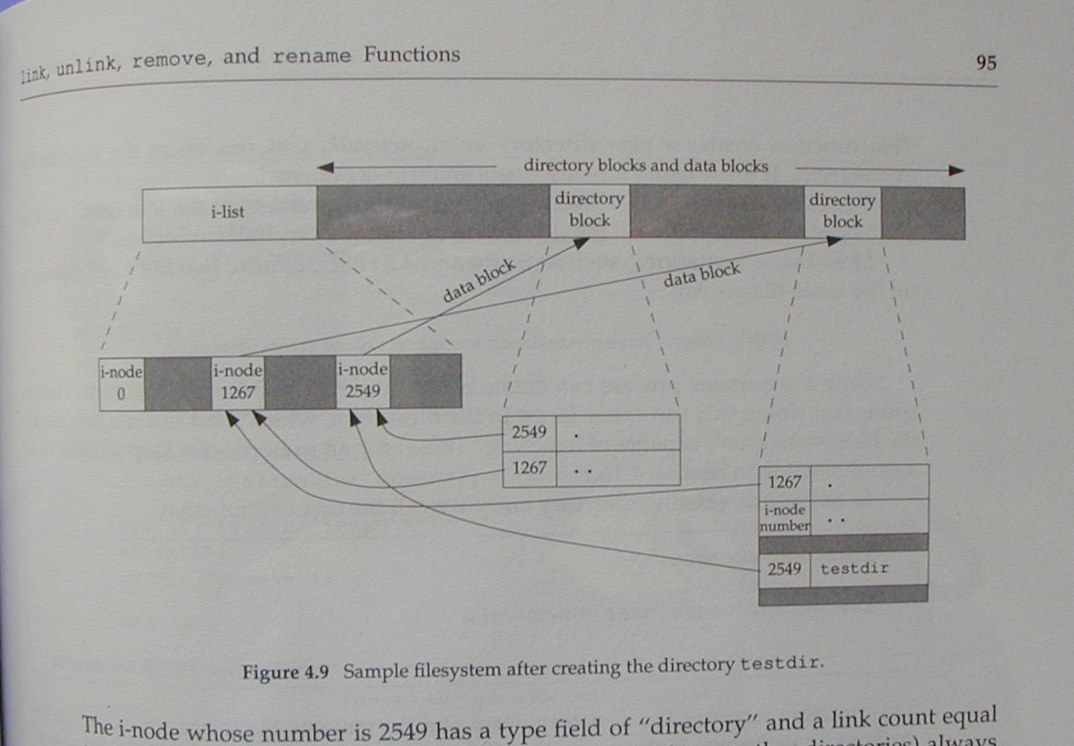

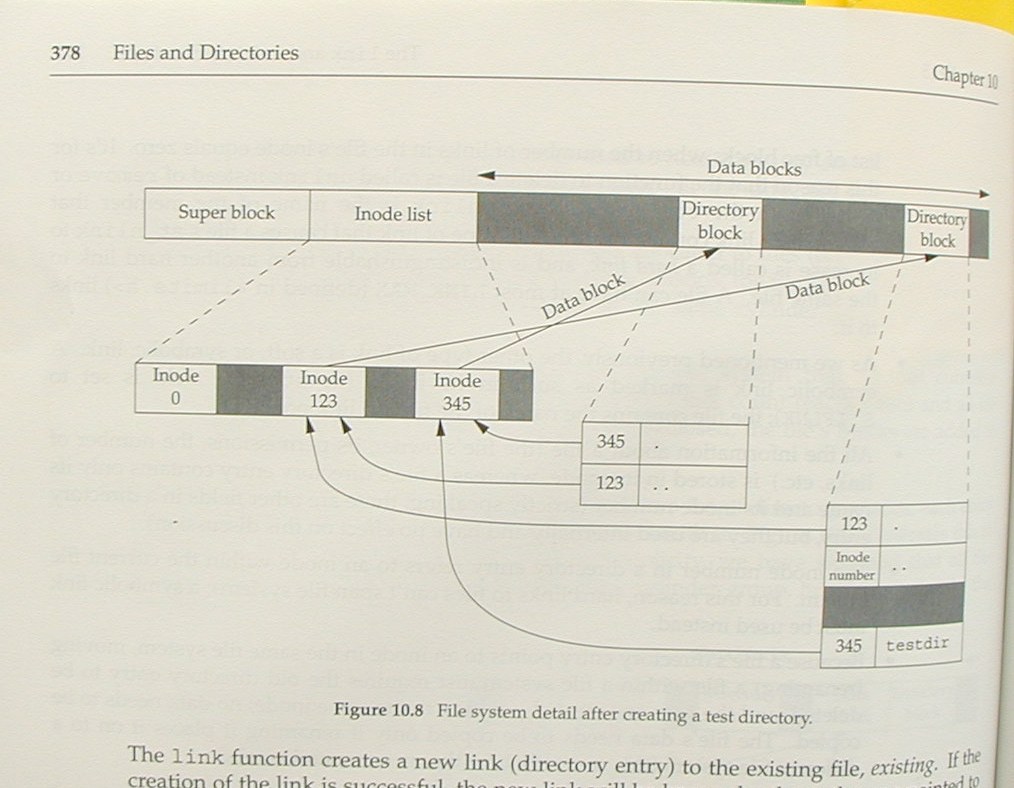

The same comments apply here.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

For this pair, there are minor changes in labeling, but they are still the same picture.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

Tables are treated as figures in both books. So there is no need for a separate section on tables. Here is an example.

| Stevens | Teer |

|---|---|

|

|

The chapter numbers on the left margin are from Teer. Most of the chapter and section titles that correspond to Stevens use the same words for the titles.

Not all of the information from Stevens is used in Teer's paraphrasing. Generally any comments regarding older systems are discarded, e.g., BSD 4.3, and where Solaris does the same as SVR4, the text is reworded to discard the reference to SVR4, etc., and describe Solaris' behavior.

Sections noted as "ok" are those where Teer has provided enough material from other sources that there is no noticeable relationship to Stevens.

Start by comparing Teer 1.3 and Stevens 1.3. At this point, they have parallel structure, but little paraphrasing. That changes. There is some, e.g., bottom of Teer p7 matches 3rd paragraph of "Filename" on Stevens p3.

Teer program 1.1 is Stevens program 1.1 (some minor changes, but at first glance a copy). The discussion for program 1.1 paraphrases Stevens, adds some new material, but is based on Stevens.

Stevens "Working Directory", p6 becomes Teer "Current Directory", p11. Stevens "Home Directory", p6 becomes Teer "Home Directory", p12, noting that the rewording regarding "placed" is not well-chosen.

Stevens section 1.4 becomes Teer 1.5. Reworded notes on file descriptor in Teer are misleading, since as Stevens notes, file descriptors are used by the kernel, provided by the process.

Compare Stevens top of p7 with Teer top of p13.

Teer program 1.2 is Stevens program 1.2 (same comment).

Teer program 1.3 is Stevens program 1.3 (same comment).

Teer section 1.6 does not resemble Stevens 1.5, except for the two programs which are adapted from Stevens.

Teer 1.7 expands on Stevens 1.7, but is less focused, since it introduces some elements of the sample programs which have already been displayed.

Stevens section 1.8 becomes Teer 1.8 (more words, same order of presentation, some paraphrasing). Teer program 1.7 is Stevens program 1.6 (same comment).

Stevens section 1.9 becomes Teer 1.9 (more words, same order

of presentation, some paraphrasing).

Teer program 1.8 is Stevens program 1.7 (Teer expands it by using

sigset rather than signal, sigset is much newer of course).

Stevens section 1.10 becomes Teer 1.10 (more words, same order of presentation, some paraphrasing).

Teer section 1.11 does not resemble Stevens 1.11.

Exercises (Teer p43, Stevens p23): the first two are paraphrased from Stevens.

This does not contain material from Stevens.

This has some overlap in content, but is not directly borrowed from Stevens.

See Stevens chapter 3.

The sections are named similarly (same order of presentation), though Teer has added Solaris-specific functions.

Stevens figure 3.1 is redone as Teer figure 4.2.

The example on Stevens p61 is paraphrased in Teer p139 by changing err_sys to err_msg and "< 0" to "== -1". The accompanying description is also paraphrased from Stevens.

See Stevens chapter 5.

Introduction (5.1) is adapted from Stevens.

First 3 paragraphs of 5.2 are adapted from Stevens.

5.3 corresponds to Stevens, but is more wordy.

Stevens section 5.4 is adapted as Teer 5.11.

Stevens section 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 5.9 are rewritten as Teer 5.4, 5.6 (little paraphrasing).

Stevens section 5.10 corresponds to Teer 5.9 (ok).

Stevens section 5.11 corresponds to Teer 5.8 (ok).

Stevens section 5.8, 5.12 corresponds to Teer 5.12 (ok: has referred to Stevens but has rewritten/expanded).

See Stevens section 6.9.

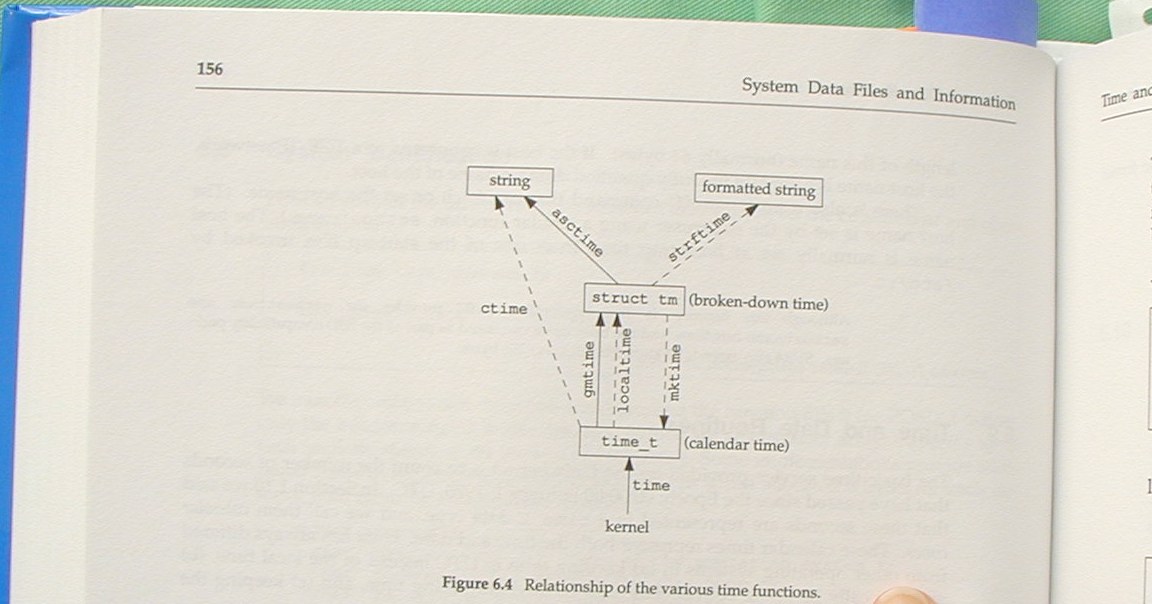

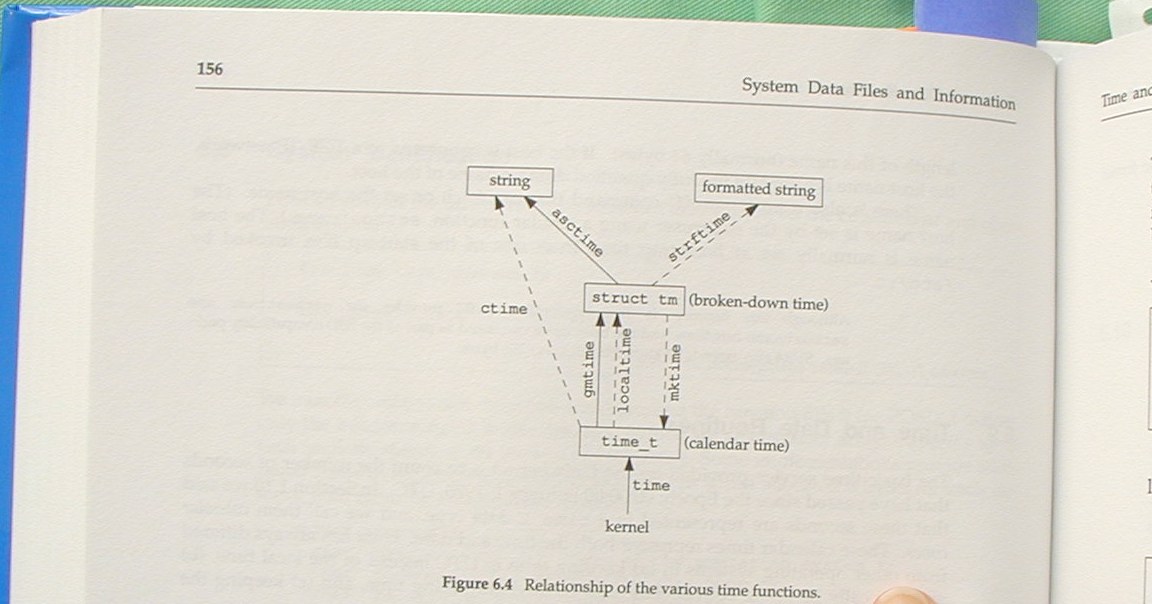

Stevens figure 6.4 is slightly modified to form Teer figure 6.1

See Stevens section 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, 8.10, 8.14.

This covers the same material as Stevens but does not appear to paraphrase or borrow content.

This does not contain material from Stevens.

This does not contain material from Stevens.

See Stevens chapter 4.

Teer 10.1 paraphrases Stevens 4.1 except for last sentence.

Teer 10.2 is new.

Teer 10.3 parallels Stevens 4.2 (does not paraphrase); oddly Teer usually orders functions alphabetically (as in the section title), but the synopsis puts them in reverse alphabetic order here. Most of the content of 10.3 is copied/adapted from Solaris manual pages (which by the way do not appear in the bibliography).

Teer 10.4 paraphrases Stevens 4.3 (some material added, but where they overlap, order, etc., are from Stevens).

Teer 10.5 paraphrases Stevens 4.4 (same comment – second half of this section is rewritten, but borrows ideas in the same order as presented in Stevens).

Stevens section 4.10 corresponds to Teer 10.6 (ok).

Stevens section 4.5 corresponds to Teer 10.7 (ok – some small pieces paraphrased, but the ordering and examples differ).

Stevens section 4.7 corresponds to Teer 10.8 (ok – same comment).

Stevens section 4.8 corresponds to Teer 10.9 (ok – same comment – Stevens example is adapted though).

Stevens section 4.9 corresponds to Teer 10.10 (ok – same comment—Stevens example is adapted though).

Stevens section 4.11 corresponds to Teer 10.11 (ok – see comment for 10.3).

Stevens section 4.12 corresponds to Teer 10.12 (same order of ideas, but not simple paraphrase).

Stevens section 4.13 corresponds to Teer 10.13 (paraphrasing).

Stevens section 4.14 corresponds to Teer 10.14 (paraphrasing in several places, e.g., compare Stevens p94 to Teer p376).

Stevens figure 4.8 is copied in Teer as figure 10.7.

Stevens section 4.15 corresponds to Teer 10.15, 10.16

(paraphrasing in several places, example is adapted).

Stevens figure 4.9 is copied in

Teer as figure 10.8.

Stevens section 4.16 corresponds to Teer 10.17 (paraphrasing, some copying, example is adapted).

Stevens section 4.17 corresponds to Teer 10.19 (ok – rewritten).

Stevens section 4.18 corresponds to Teer 10.20 (different

text, but same ordering of the items – not alphabetic).

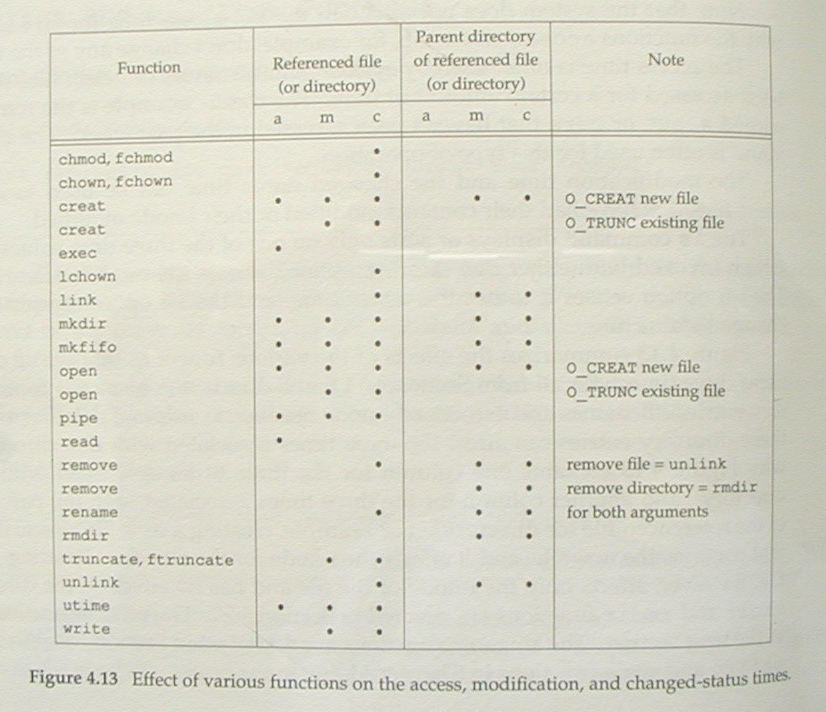

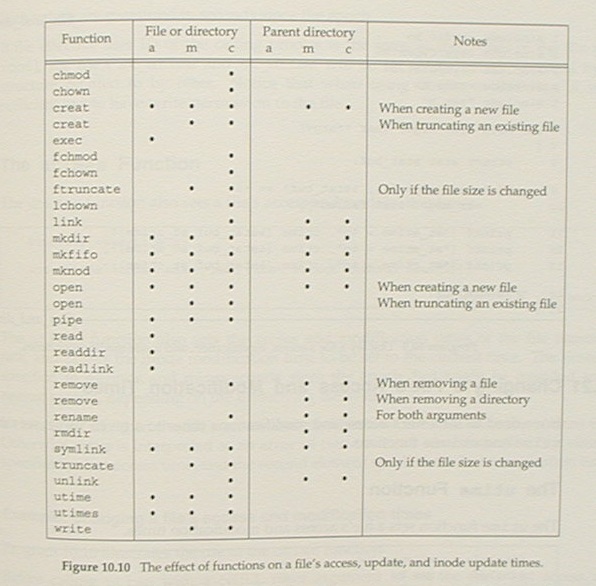

Stevens figure 4.13 is extended

in Teer as figure 10.10.

Stevens section 4.19 corresponds to Teer 10.21 (ok – rewritten).

Stevens section 4.20 corresponds to Teer 10.22 (ok – rewritten, though not well done: example now contains a coding error).

Stevens section 4.21 corresponds to Teer 10.23 (ok – rewritten).

Stevens section 4.22 corresponds to Teer 10.24 (first paragraph paraphrased, example 4.8 is adapted as 10.14 in Teer, synopsis blocks are copied, last paragraph paraphrased – the point of the second example which is not obvious from the code, and which is not necessary to this section).

Stevens section 4.23 corresponds to Teer 10.26 (the example on Teer p409 is adapted with minor changes from Stevens p11, otherwise the text is different – Stevens is clear, Teer not).

Stevens section 4.24 corresponds to Teer 10.27 (the synopsis block is copied from Stevens, but the text is different).

Stevens exercises on p118 are a

source for Teer exercises p416 (4.3 10.2, 4.5 10.3, 4.6 10.4, 4.7

10.5, 4.14 10.6).

Exercise 10.1 which has no counterpart in Stevens is poorly

chosen.

This does not contain material from Stevens.

See Stevens chapter 11.

Stevens section 11.1 corresponds to Teer 12.1 (paraphrased, with additions by Teer).

Stevens section 11.2 corresponds to Teer 12.2 (paraphrased,

with additions by Teer).

Stevens figure 11.1 is Teer 12.1 (rotated by 90 degrees).

Stevens figure 11.2 is Teer 12.2 (minor changes).

Stevens figure 11.3 is Teer 12.3 (extended by new columns but

same purpose).

Stevens figure 11.4 is Teer 12.4 (same structure, minor

changes).

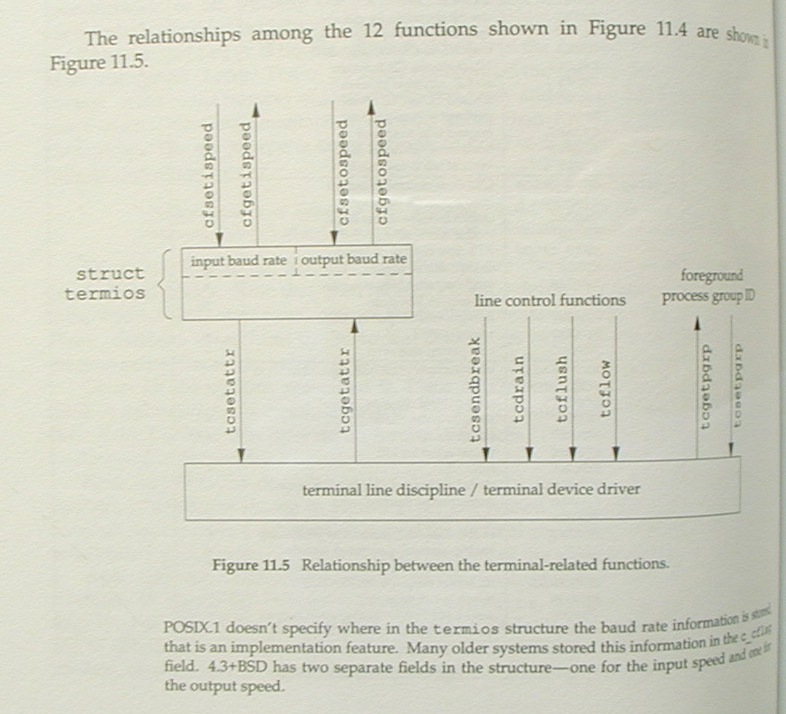

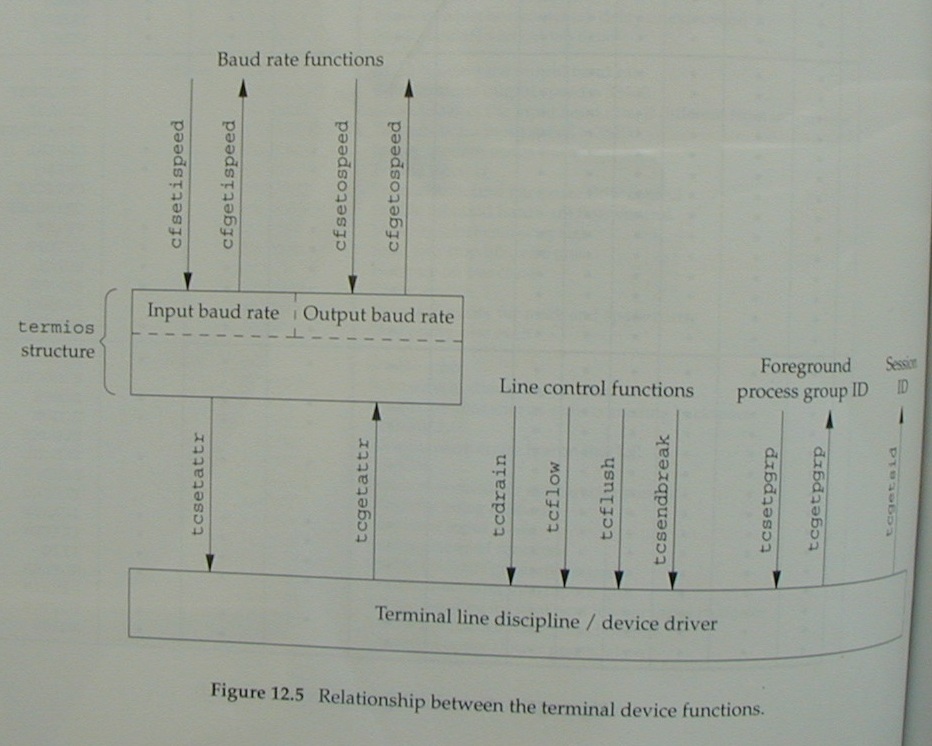

Stevens figure 11.5 is Teer 12.5

(same structure, minor changes).

Stevens section 11.3 corresponds to Teer 12.3 (paraphrased,

with additions by Teer).

Stevens figure 11.6 is Teer 12.6 (some columns different but same

purpose).

Stevens section 11.4 corresponds to Teer 12.4 (paraphrased,

the synopsis block is copied from Stevens).

Stevens program 11.2 corresponds to Teer 12.2 (Teer does add some

functionality to steven's example).

Stevens section 11.5 and 11.6 corresponds to Teer 12.5 (paraphrased, with additions by Teer).

Stevens section 11.7 corresponds to Teer 12.6 (paraphrased).

Stevens section 11.8 corresponds to Teer 12.7 (ok – no direct borrowing).

Stevens section 11.9 corresponds to Teer 12.8 (ok – no direct borrowing, e.g., example program is for ttyname_r rather than ttyname).

Stevens section 11.10 corresponds to Teer 12.9 (paraphrases, adapts the example program by removing the signal handling stating that signals haven't been discussed yet, although the index gives several counterexamples, and also adds some useless text about encryption which is dealt with superficially in Teer's book).

Stevens section 11.11 corresponds to Teer 12.10 (paraphrases, incorrectly uses the term "intercharacter" to replace Stevens' "interbyte").

Stevens figure 11.7 is Teer figure 12.8 (one word changed, but that makes the description incorrect).

Stevens program 11.10 is adapted as Teer program 12.7.

Stevens program 11.11 is adapted as Teer program 12.8.

Stevens section 11.12 corresponds to Teer 12.11 (paraphrases,

except comment about SVR4 and BSD is replaced by comment about

X).

Stevens program 11.12 is adapted as Teer program 12.9.

Stevens section 11.13 corresponds to Teer 12.12 (paraphrases, except section title is – for a change – modified). Note especially that the references are copied from Stevens, including Goodheart which has been out of print since the mid-90's. It was topical for Stevens to use it; it is evidence that Teer copied this section. That, and the poorly constructed replacement for the last sentence in the section prompted me to look closely at the bibliography.

Stevens section 11.14 corresponds to Teer 12.13 (paraphrases).

Stevens exercise 11.1 is Teer 12.2.

Stevens exercise 11.3 is Teer 12.1.

See Stevens chapter 12.

Stevens 12.2 corresponds to Teer 13.2, (paraphrased, omitting the historical notes as usual).

Stevens 12.3 corresponds to Teer 13.3, 13.4, 13.6, 13.7 (paraphrased). Teer's rewording of definition for record locking is poor. Teer omits historical notes from Stevens which are relevant even to Solaris.

Teer 13.4 gives an incorrect prototype for fcntl in the synopsis; the Solaris-specific discussion of the 3rd parameter is poor. Teer program 13.2 copies Stevens 12.2, renamed and removed comments. Teer program 13.3 copies Stevens 12.3, renamed and add a struct in the wrong place, making it useless.

Teer 13.5 discusses lockf (not in Stevens).

Teer 13.6 copies the dining philosophers example from another source than Stevens (but I don't see anything suitable in Teer's bibliography). Here is an interesting reference which shows where to start looking. However Teer program 13.4 is adapted from Stevens 12.4.

Teer 13.7 is adapted from Stevens p373. Teer omits content from Stevens p374 to top of 378.

The first part of Teer 13.8 (p521) is adapted from Stevens p378-379. Notes on performance and program 13.5 do not appear in Stevens.

Teer 13.9 corresponds to Stevens 12.4 p383-384 (but is a disordered rewrite). Program 13.6 is adapted from Stevens 12.9.

Teer 13.10 corresponds to Stevens 12.4 p385-386 (but is a disordered rewrite).

Teer 13.11 corresponds to Stevens 12.4 p386-387 (but is a disordered rewrite). Figure 13.7 is adapted from Stevens 12.10 (changes "yes or no" to "don't care").

Teer 13.12 corresponds to Stevens 12.4 p392 (but is a disordered rewrite).

Teer 13.13 corresponds to Stevens pp 387-391, but is actually

paraphrased from Solaris manpages, e.g.,

streamio (7i). Teer program 13.8 is adapted

from Stevens program 12.10.

Teer 13.14 corresponds to Stevens pp 391-394. Teer reorders this, putting the discussion of read before write. However (contrary to Teer's usual practice), the options listed are in the same non-alphabetic order as Stevens. And the streamio manpage does not list some of those listed by Stevens, e.g., SNDPIPE.

Teer 13.15 paraphrases Stevens 12.5. The talkd program in Teer corresponds to the modem dialer in Stevens. Noting that renaming, Teer figures 13.9 and 13.10 are adapted from Stevens 12.11 and 12.12.

Teer 13.16 corresponds to Stevens 12.5.1 (but is a disordered rewrite). Some parts are paraphrased (cf: Teer p541 with Stevens p397 and Teer p542 with Stevens p399-400).

My own review stops at this point, in the middle of chapter 13. Reviewing takes time. I have incorporated comments from Gunnar Ritter and Ian Clarke for the remaining chapters.

See Stevens chapter 7.

See Stevens chapter 8.

Ian Clarke comments on this chapter.

See Stevens chapter 9.

Ian Clarke comments on this chapter.

See Stevens chapter 10.

See Stevens chapter 13.

See Stevens chapter 14.

See Stevens chapter 14.

See Stevens chapter 15.

Gunnar Ritter notes:

As Ian Clarke has mentioned, the chapter on doors (22, page 951 etc.) is derived from volume 2 of Stevens "UNIX Network Programming, Second Edition: Interprocess Communications" (Prentice-Hall, 1999), chapter 15, page 355 etc. This is again plagiarism in my opinion because Teer does not explicitly mention his source for the derived parts; I don't think just having it in the bibliography is enough for all of the following:

and lists several instances:

Teer 22.1, pages 951-953 are from Stevens 15.1, pages 355-357.

Teer figure 22.1 is Stevens fig. 15.1.

Teer pages 954-955 are from Stevens pages 363-364.

Teer page 956 is from Stevens pages 362-363.

Teer pages 960-961 are from Stevens pages 367-369.

Teer pages 962-965 are from Stevens pages 375-379.

Teer pages 977-978 are from Stevens page 384.

Teer pages 979-980 are from Stevens page 386.

Teer pages 983-985 are from Stevens pages 388-390.

Teer pages 985-986 are from Stevens pages 390-391.

Teer page 986 last paragraph is from Stevens page 395.

Teer page 992 is from Stevens pages 397-398.

Teer exercise 22.1, page 993 is Stevens 15.4, page 398.

Same comment applies to 22.2 (derived from Stevens exercise 15.6), 22.3 (derived from Stevens exercise 15.8), 22.4 (derived from Stevens exercise 15.9).

concluding with

So Teer has really plagiarized from two books of Stevens.

See Stevens chapter 19.

Ian Clarke comments:

I had a look at that chapter (chap. 23): most of the diagrams are the same or very similar (and in the same order), there are a number of rather similar looking paragraphs and a general order of presentation that is very similar to Stevens (chap. 19). Most notably, the main example program of the chapter (pty.c) is the same program (with some modification) as Stevens wrote.

See Stevens Appendix B.

See Stevens Appendix C.

First two exercises from chapter 1 are copied from Stevens.

Here are Gunnar Ritter's comments. Except as noted, I have made only minor changes to present them on this webpage.

Although Teer does not mark the material he has borrowed from Stevens, the first sentence of the publisher's book description which is also printed on the back cover is "In the tradition of W. Richard Stevens' Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment, this book offers comprehensive, practical guidance for systems programmers." From Teer's preface, the reader learns "Despite the word 'Solaris' in the title, this book is suitable for programmers of any UNIX or UNIX-like operating system (that being said, some of the features we describe are specific to Solaris)" (page xxxi, Teer's emphasis).

This claim is important for the buyer and reader. Many people are writing programs for Unix-like environments today. But Solaris is only one of the Unix-like environments available, and, according to many reports, it might not even be the prevalent one of them. So many people are interested in learning Unix programming but are not using a Solaris system. Moreover, it is common to keep programs portable between the various Unix-like environments because the effort of doing so is not too high, but the gain of programs that run on e.g. Linux, Solaris, and BSD is. This applies to both Open Source and commercial programming. Thus even if somebody learns programming on a Solaris system, chances are high that he wants to write portable programs, or is even required to do so by his employer.

From the second sentence cited above, it is clear that Teer claims that his book is useful for learning how to write portable programs. And from the first sentence, it is clear that this is to be done in the tradition of Steven's APUE. Now Stevens had pursued a very elaborate but successful way of ensuring portability: He had actually tested his example programs on a variety of then-contemporary Unix systems, as described on page xvii of his preface. In contrast, Teer tested his programs only on the Solaris platform, as described on page xxxv of his preface, and much of his sample code actually cannot be compiled e.g. on Linux or BSD systems. This would certainly have been excusable if such code had been marked, i.e. if there had been a set of portable base examples and another set of examples that introduce special Solaris functionality. But there is no such distinction in Teer's book. As far as the examples are concerned, a Linux or BSD user of today can thus just as well use Stevens' book as Teer's; some of the examples do work with both books, and for those that do not, the reader has to determine the reason on his own.

Teer's main method of providing portability information is the function availability table following page 1104. The table covers all versions of Solaris from 2.5 to 9, and a number of standards, all of them from the 80s and 90s, and all based on the C standard from 1989 and the POSIX.1 standard from 1990. These are the very standards on which Stevens' book was based; Teer explicitly dispenses with information about the recent C standard from 1999 and the recent POSIX.1 standard from 2001 because they were still not supported by Sun with Solaris 9 (they are supported from Solaris 10 on, though). As far as standards-based programming is concerned, Teer's book has thus not much more to offer than Stevens'.

Moreover, Teer's method of presenting the standards is

impractical. For every interface he learns, Teer's reader has to

consult the table if he is interested in its portability. Stevens

presents such information in-line. Still worse, Teer's table

provides only a function summary; it lacks any information about

defined constants, structure fields etc., and Teer gives such

information only sporadically within the text (e.g. for the flags

for open() on page 127). Thus even if a function is

contained in the table, the reader often cannot determine if the

way it is called conforms to the standard. The listing of

deficiencies in Teer's book below gives some prominent cases.

It must thus be concluded that, unless one sticks with writing programs for Solaris only, Teer's book is inferior to Stevens'. The fact that it was published eleven years later is nearly irrelevant in this respect.

The following table lists some individual deficiencies of the book, most of them concerning portability, but also some generic inconsistencies. Page numbers are from Teer.

| Page | Comments |

|---|---|

| 8 |

Teer introduces MAXNAMELEN here (why not the

POSIX constant NAME_MAX?) but later writes on

page 283

This is inconsistent. |

| 33 | long double occupies 96 bits on Solaris/i386

with Sun C, not 128. |

| 99 |

Teer says

This comes straight from the WARNINGS section of

Stevens' position "implementations exist for a wide

variety of systems" (page 171) makes much more sense. In

particular, |

| 175-176 | The printf conversions %wc and

%ws are proprietary to SVR4 derivatives but Teer

does not mention this anywhere. This is particularly bad

because the lack of portability will only be noticed at run

time on most platforms later. |

| 184-185 | Teer does not explain why fgetpos() and

fsetpos() are available and why they are of

little use on Unix. Stevens did (page 136). This is not

helpful to a novice who might ask "Now should I use fseek()

or fsetpos()?". |

| 268-269 |

The description of utmp/utmpx and wtmp/wtmpx only applies

to Solaris, without any remark about the various

portability constraints in this area. This culminates with

(i.e., |

| 276 |

Teer says that the nodename field of

struct utsname contains

Stevens remarked on page 154

which is still relevant today and still causes a lot of

confusion for novices. Teer mentions the possible lack of

domain information only for

|

| 325 | Teer describes the /proc filesystem but does

not even mention that its structure is totally different on

other platforms. An actual description of other structures

may well be outside the scope of the book, but it would not

have hurt if he had just made a remark about that. |

| 334-335 | Teer describes getloadavg() but does not

mention that the constants such as LOADAVG_1MIN

and the <sys/loadavg.h> header are Solaris specific.

(The call is otherwise portable to BSD at least.) Stevens had

probably written a portable wrapper function for this because

the information can be retrieved on nearly any platform in

some way. |

| 337 |

Teer claims that

But on pages 864-865 he devotes an entire section to Denial of Service Attacks and makes at least some notes on how to avoid them. He never mentions algorithmic complexity attacks which are definitively relevant for application programming. The chapter on Secure C Programming thus is not only incomplete, it is even inconsistent with the rest of the book. |

| 344-346 | Teer devotes three pages and a complete sample program on

how to break out of a chroot jail. The example is horribly

stupid though because all what is necessary for the programm

to defend from this particular "attack" is to insert a

chdir("/"); after the first call to

chroot(). What Teer presents is thus a weakness

in his sample code, not a weakness in the chroot call. What

is worse is that there are actual ways to break out on

Solaris that are not much more difficult to perform and

against which there is no way to defend if root privilegues

can be obtained inside the chroot, most prominently mounting

/proc and using /proc/1/cwd to

break out, or using /dev/mem to access the

kernel structures directly. But the reader does not learn

about the real dangers from Teer's book. |

| 357 | Teer does not mention that the st_fstype

field of struct stat is only available on SVR4

derivatives, and that the block size for the

st_blocks field depends on the implementation

(cf. Stevens page 80). |

| 363 | In the note in small type, Teer apparently describes the effects of the sticky bit on directories but does not mention what his description applies to. |

| 512 | Mentioning that mandatory locking is nonportable would not have hurt. |

| 556 | Teer describes sendfile() but does not

describe that the particular interface originates from Linux.

No history notes, no portability notes. |

| 564-565 | Teer does not mention the portability constraints concerning anonymous mappings. |

| 644 | The WNOWAIT constant is not in POSIX but the

reader cannot learn this from Teer's book. |

| 687 | Teer does not mention that the way to obtain a controlling terminal is implementation-specific (cf. Stevens page 246). |

| 719 |

Teer describes sigset() as "the signal

function's reliable counterpart" but does not describe the

various portability constraints of it. BSD systems

generally did not provide it until very recently (except

for very old code that had been left out since 4.3BSD); on

Linux with GNU libc or uClibc, one must define

_GNU_SOURCE or _XOPEN_SOURCE to

get its prototype; Linux with diet libc, libc5 or older

does not provide it at all. All would have been fine if

Teer had provided his own implementation of it (and the

related functions) using the portable

sigaction() interface; but he did not. Teer

frankly admits that he does not know about all of this on

page 746 where he writes

It is clearly not in Stevens' tradition to speculate about portability instead of making the required tests. |

| 720 |

Teer claims that

This is wrong because BSD |

| 753-754 | Some of the flags for sa_flags in

struct sigaction are from POSIX, some are from

SUSv2, and some are Solaris-specific, but the reader does not

learn this from Teer's book. |

| 952 |

Teer writes that

But this project is not being actively developed anymore; its last update was on January 5, 2003 for Linux 2.4.18, more than one and a half year before the publication of Teer's book. Now Teer does provide a portability hint as an exception here, and then it can easily lead the reader to the wrong assumption that anybody was actively developing an implementation of doors for Linux. |

| 1045 |

The chapter An Internationalization and

Localization Primer has almost nothing about

multibyte character encodings. It even leads the reader to

a wrong direction here:

But one does not use hard-coded international character sets with the C/Unix/Solaris locale mechanism. On page 1046, Teer writes that

But Teer in fact omits one of the most intricate consequences of internationalization and misleads his reader instead, which is not acceptable even in a short summary. |

| 1104-1115 | Teer's Function Availability table

contains a "POSIX" column that "refers to the 1996 edition of

POSIX 1003.1". What Teer does not mention is that this

edition provides a couple of implementation options. He has

arbitrarily chosen these options for composing his table;

functions available with the

_POSIX_THREAD_SAFE_FUNCTIONS option such as

getc_unlocked() and getpwnam_r()

are marked in the POSIX column, but fsync() from

_POSIX_FSYNC or mmap() and

ftruncate() from

_POSIX_MAPPED_FILES are not, even though Solaris

offers all three options. |

Here is a list of the subsequent discussions in newsgroups about the Solaris Systems Programming book.

Thomas Dickey Apr 25, 8:22 pm show options Rich Teer <rich.t...@rite-group.com> wrote: > Yes, see the setbuf man page. I also deal with the effects of I/O buffering > in my book, Solaris Systems Programming. hmm - Stevens section 5.4 corresponds to Teer section 5.11 (this would make a nice example for side-by-side display on a webpage ;-)

statvfs() function. Comparing pages 439-440, it

is apparent that this is simply a case where he paraphrased

the Solaris manpage, but overlooks some of the interesting

details. Teer, for example, refers to the struct members as

unsigned long. But Sun's manpage says

(equivalent but not the same) u_long. Checking

the header file, I see that it says unsigned long. But - this

would have been more useful in the book than a regurgitation

of the manpage - the header file also details support for

32-bit and 64-bit applications.

In the broader context of the newsgroup discussion, Teer demonstrates that he is unaware of the differences between Solaris and the X/Open descriptions of this function.

mkstemp(). The coverage is limited

to this one line (page 109):

a race condition exists between generating the name of the file and actually creating it

There is no discussion of the implications of this, e.g., that another process might create a file with the same name, or a symbolic link to an existing file. Since the same information in that section is obtained from the Solaris manpage, it is likely that Teer simply paraphrased the manpage:

The mkstemp() function replaces the contents of the string pointed to by template by a unique file name, and returns a file descriptor for the file open for reading and writing. The function thus prevents any possible race condition between testing whether the file exists and opening it for use. The string in template should look like a file name with six trailing 'X's; mkstemp() replaces each 'X' with a character from the portable file name character set. The characters are chosen such that the resulting name does not duplicate the name of an existing file.

The remainder of this paragraph is found on page 110, using the wordiness and imprecision typical of Teer's paraphrasing:

The mkstemp function creates and opens a temporary file, returning the file descriptor of the newly created file. Like the mktemp function, template is used to create a unique filename. The trailing six X characters of template are replaced by a string that uniquely identifies the file (if a unique filename can't be generated, a NULL pointer is returned). The resulting filename is then opened for reading and writing, thus avoiding the hazard that would result if we performed the tasks ourselves.